Ulrich GebertUR

Ulrich Gebert examines in his metaphoric image-cycles and installations the relation of human beings to their environment, in particular to nature – whether civilized or untouched. However, he does not pursue the ‘romantic’ idea of a reunification between culture and nature but rather creates in form and content a background that critically questions our living conditions. Starting from the question of how the individual or society inscribes into the habitat, Gebert conflates in his works our projection ideas on nature and culture with the power of the image.

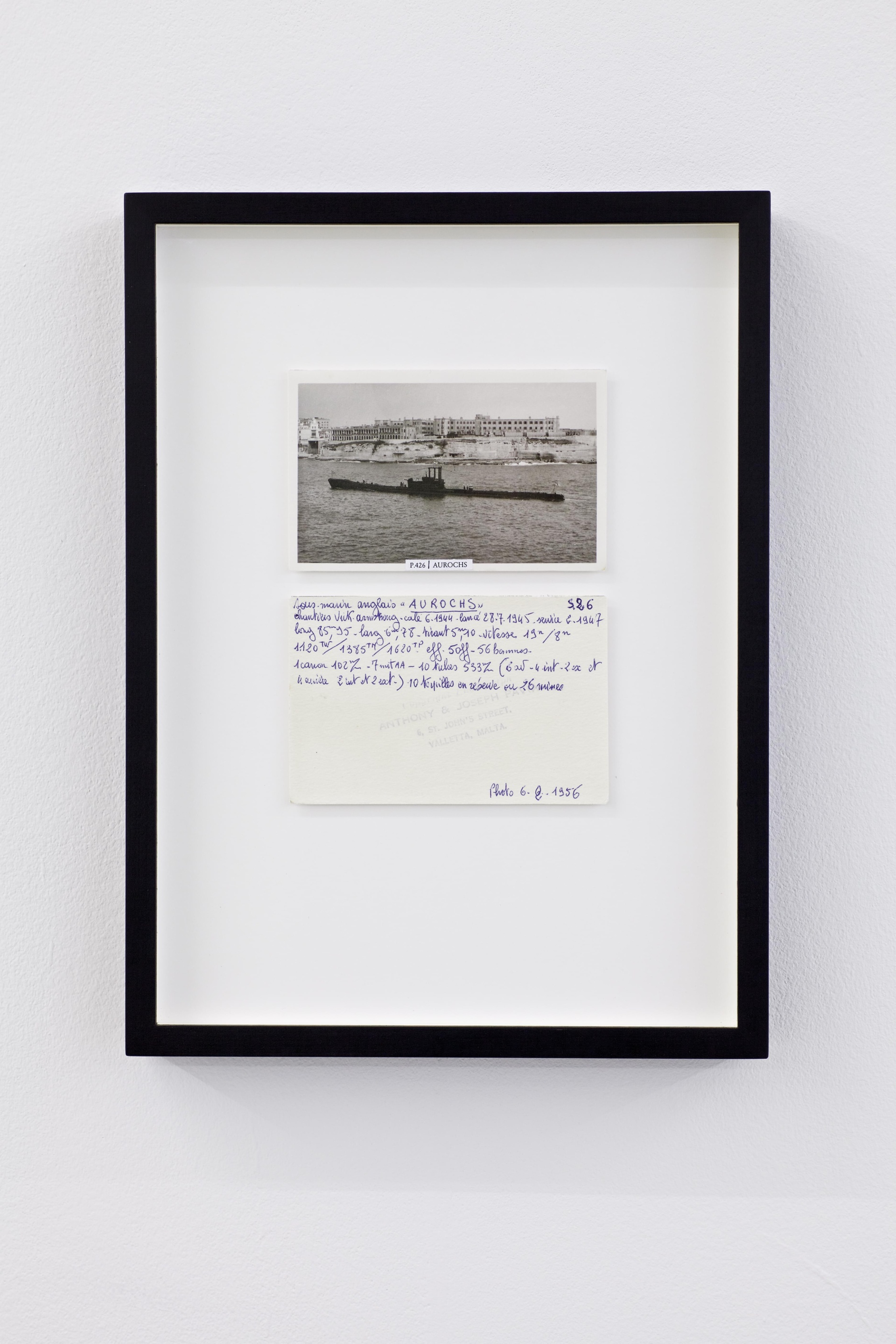

In his new body of work UR he deals with terms of reconstruction, authenticity and the question of the original tied to the longing for a reliable and tangible (ur-) state of being. It equally addresses the human reflex of ascribing, projecting and augmenting as ideas and clichés of an untouched idyllic nature.

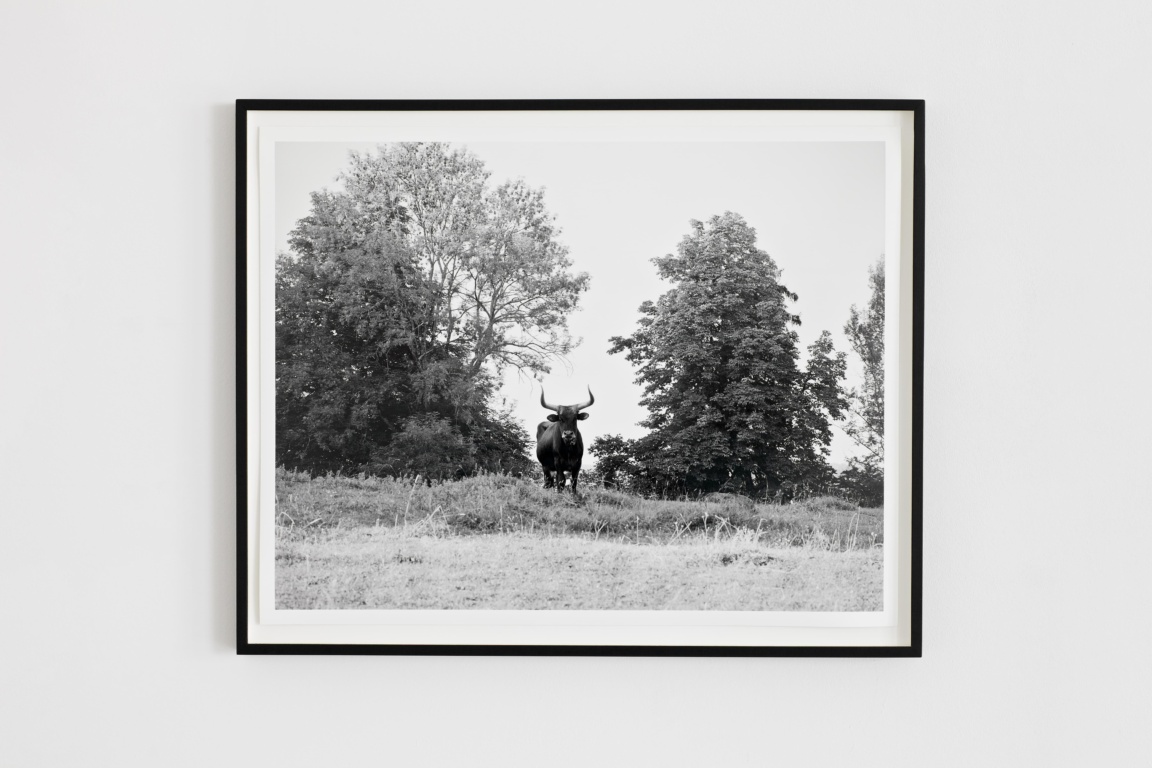

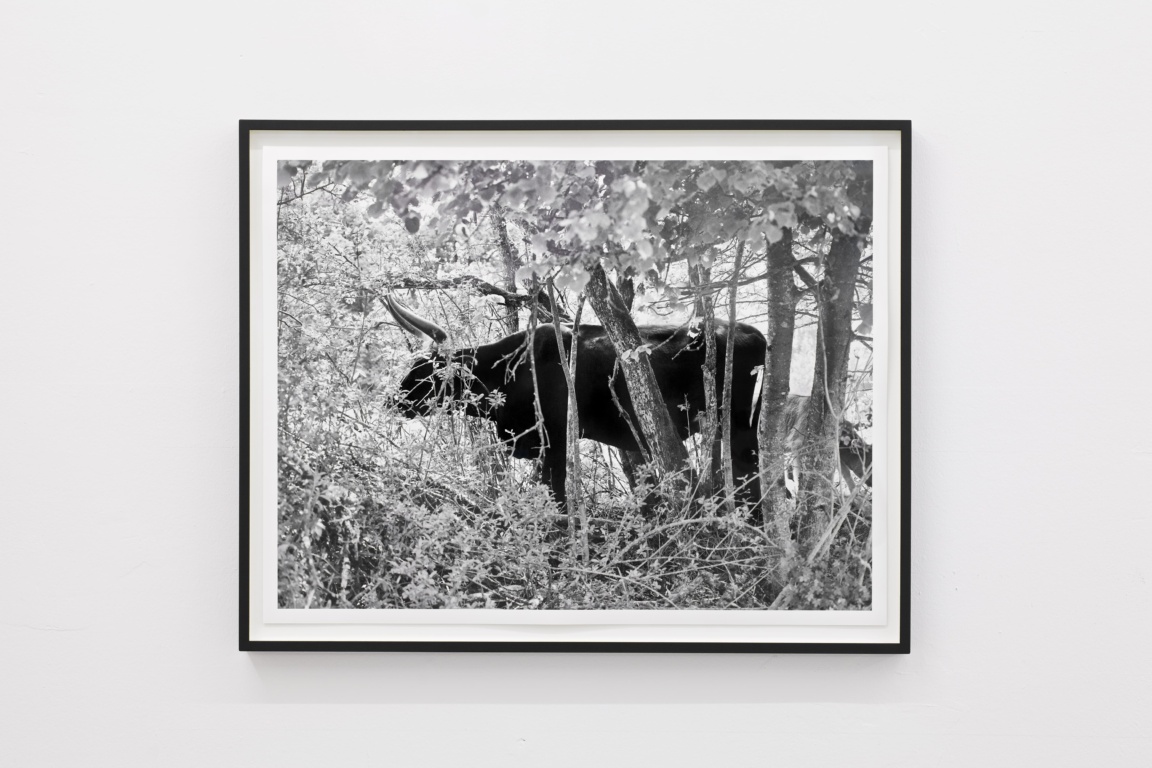

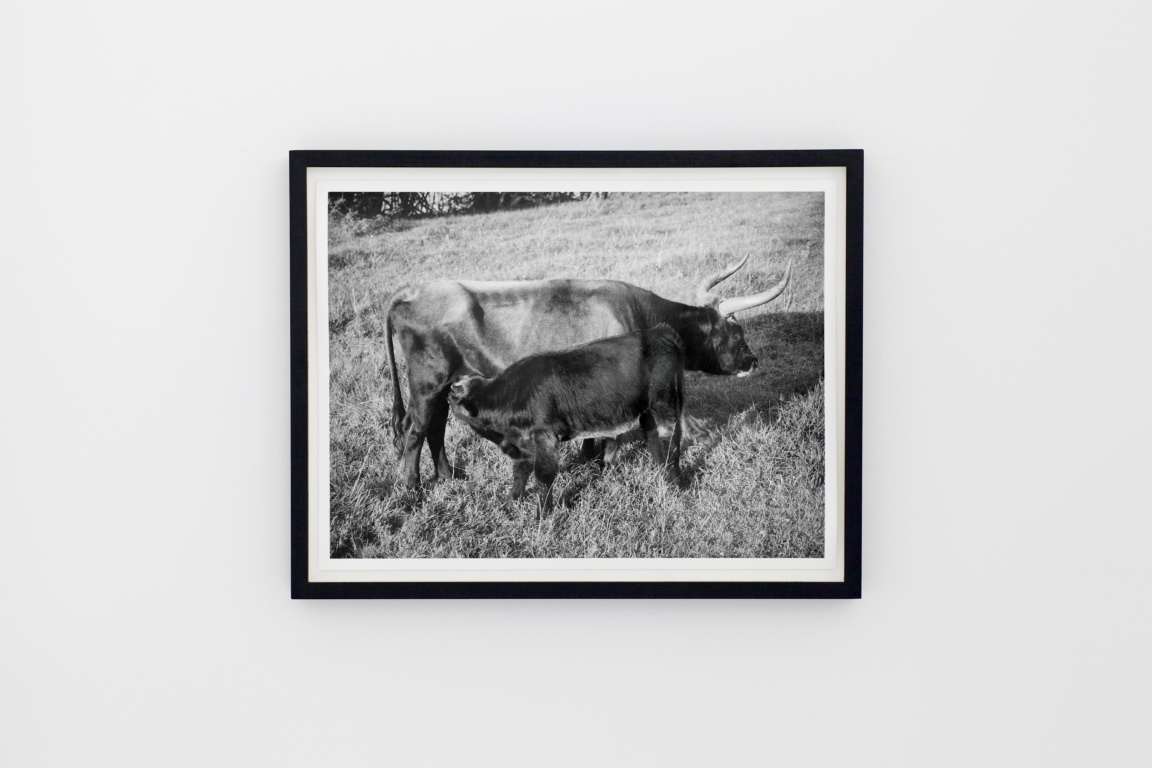

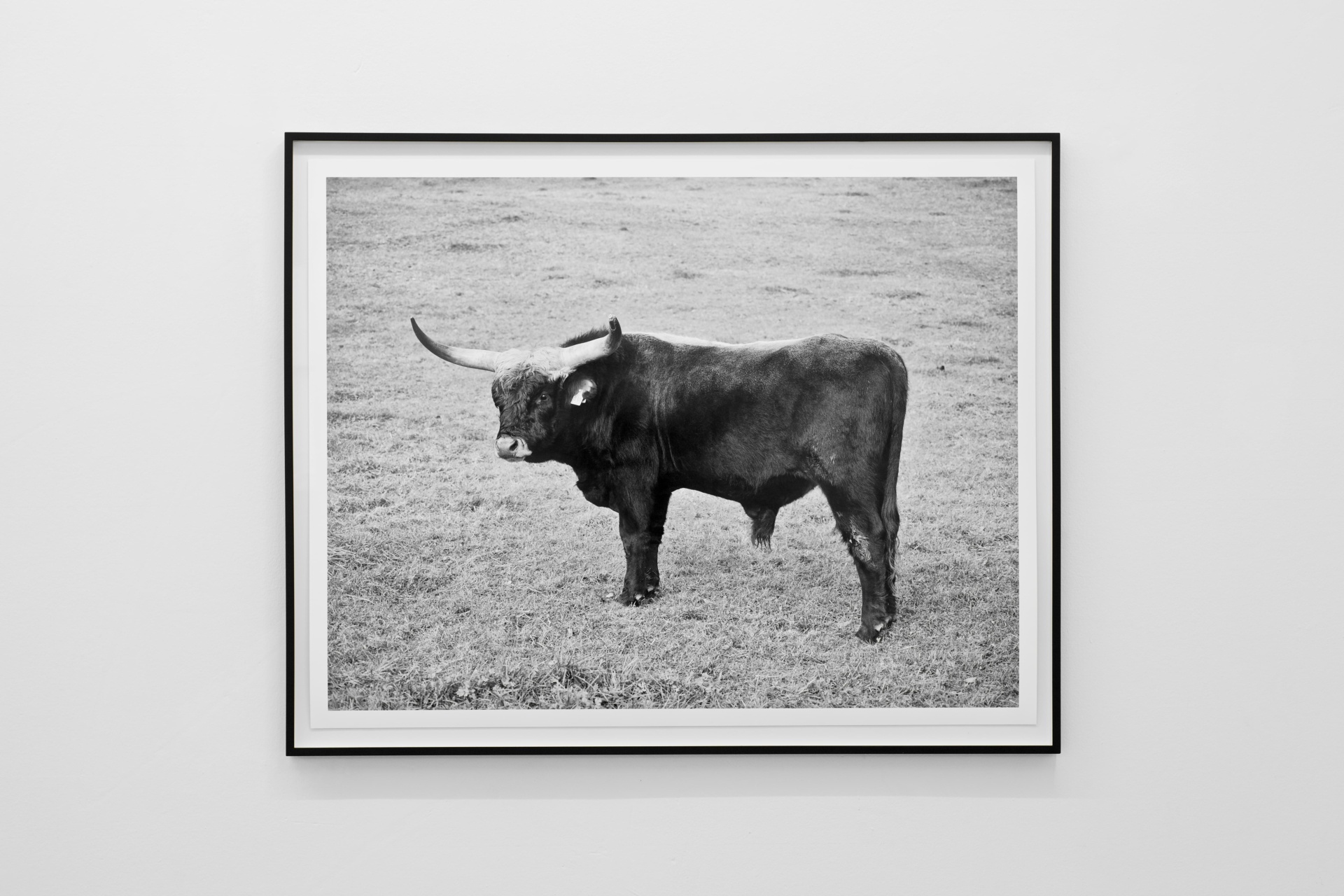

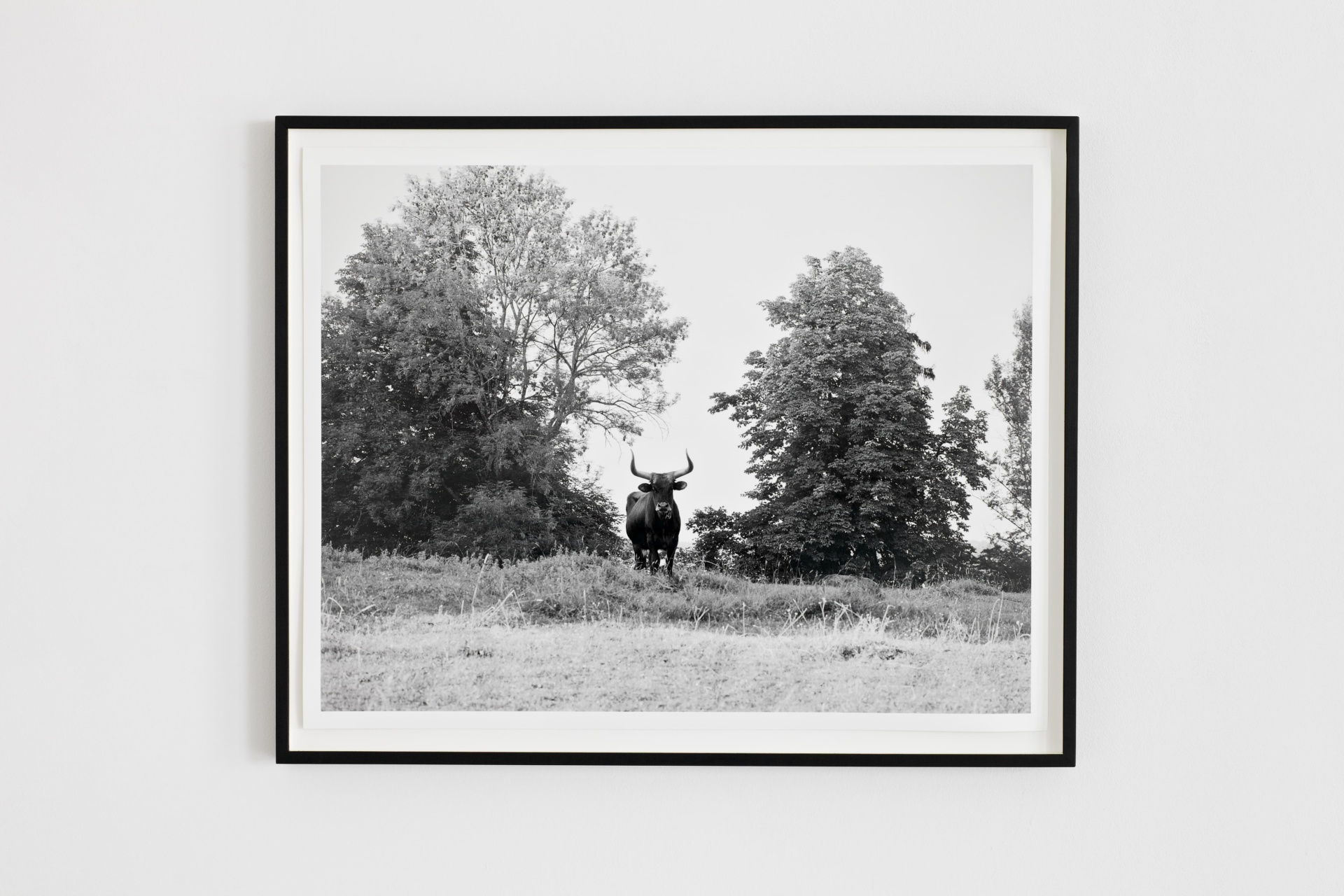

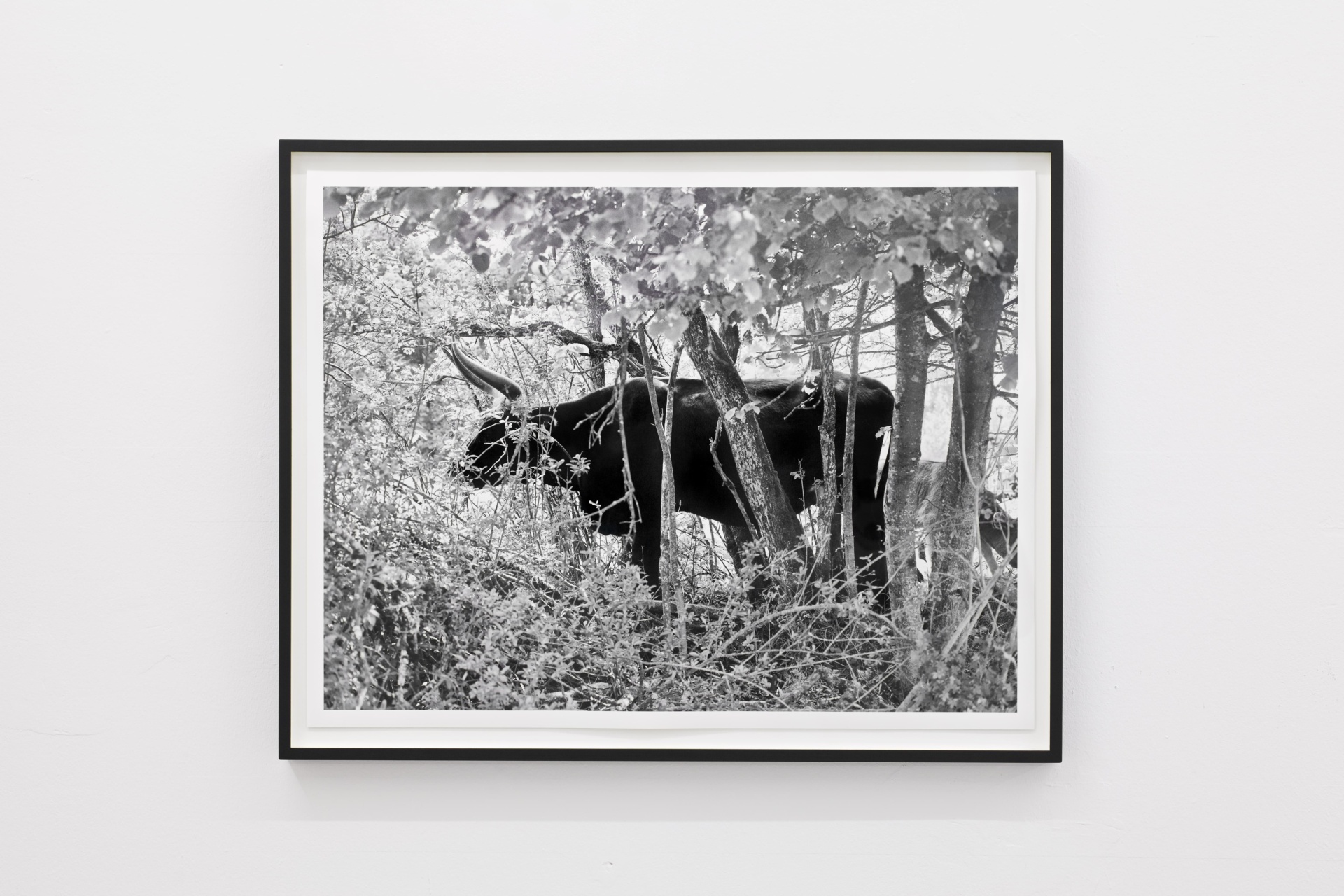

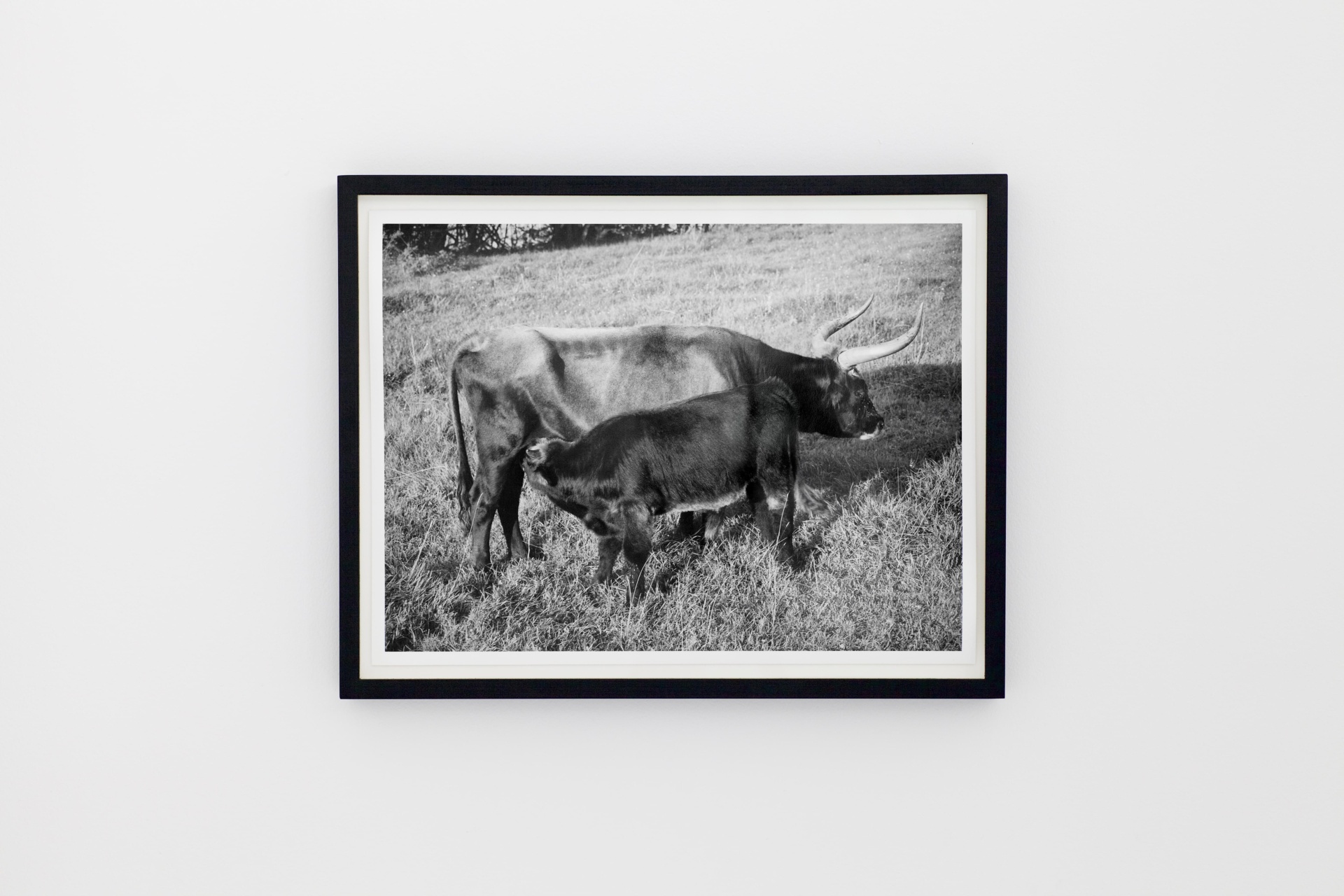

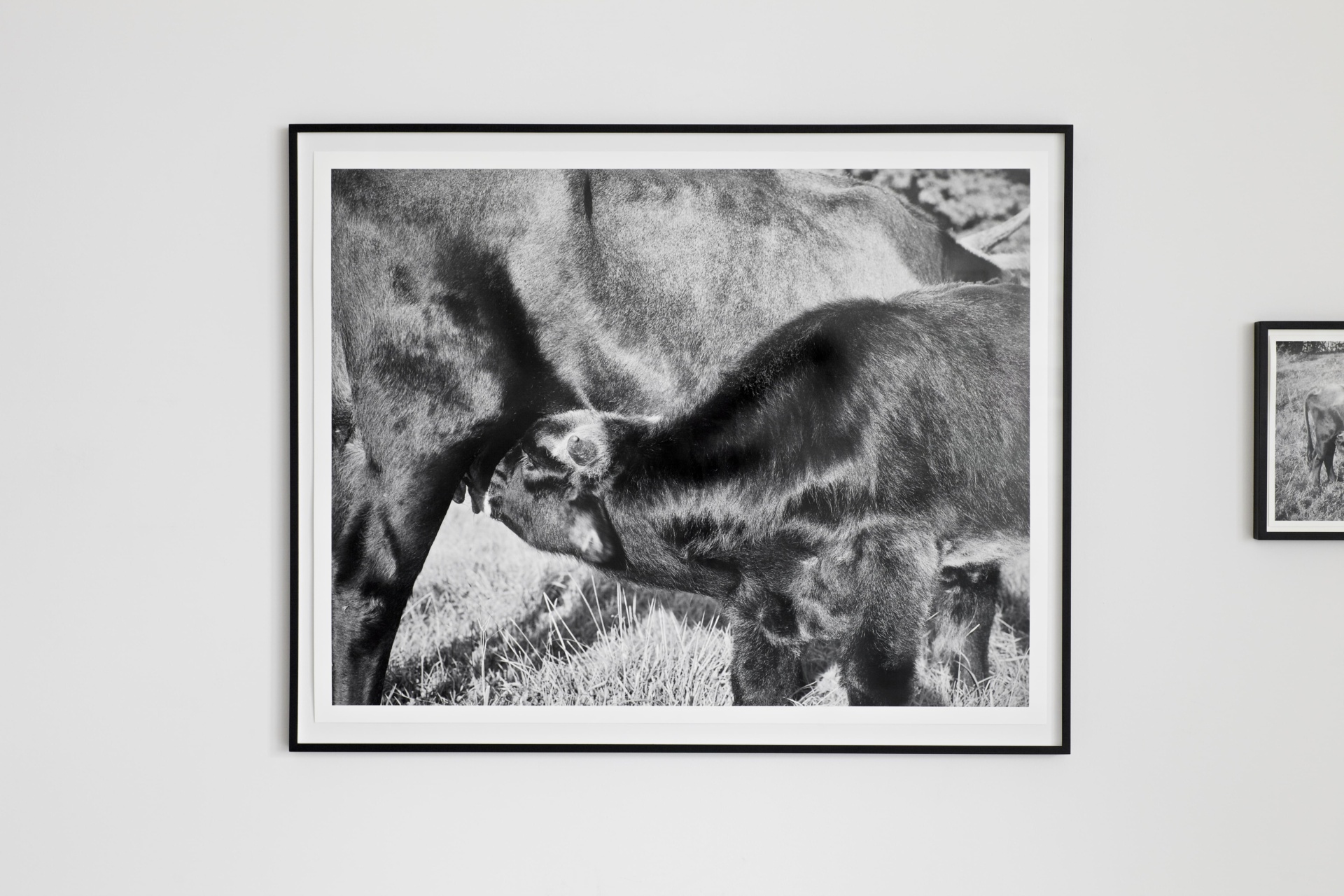

For this new series Gebert has observed a herd of rebred aurochs on the Bavarian island of Wörth in lake Staffelsee, picturing the cattle as a site of tabula rasa and “incarnated monument for human empowerment phantasies” (Ulrich Gebert). Based on an in-depth research of the historical topic on the rebreeding attempts for the aurochs that the brothers Lutz and Heinz Heck started in the late 1920s, the discussion reveals parallels to current discourses in cultural theory in spite of the time distance to this political period. It addresses not only the tension between nature and artificiality but also the symbiosis of the allegedly natural and its disclosure as cultural construct. The subject of the aurochs as ur-image in its most literal sense looks back to a thousand year old tradition, the cave paintings of Lascaux and Chauvet being its testimonials. And yet, there is no faithful depiction of it known to us. Breeding programs as in landscaped grazing projects can only convey an idea of how the extinct Ur-cattle once has looked. But still, the black/white photographs of Gebert evoke an unassailable moment of authenticity: at once heroic and yet somehow intimate they almost develop a portrait-like presence with a tint of melancholy.

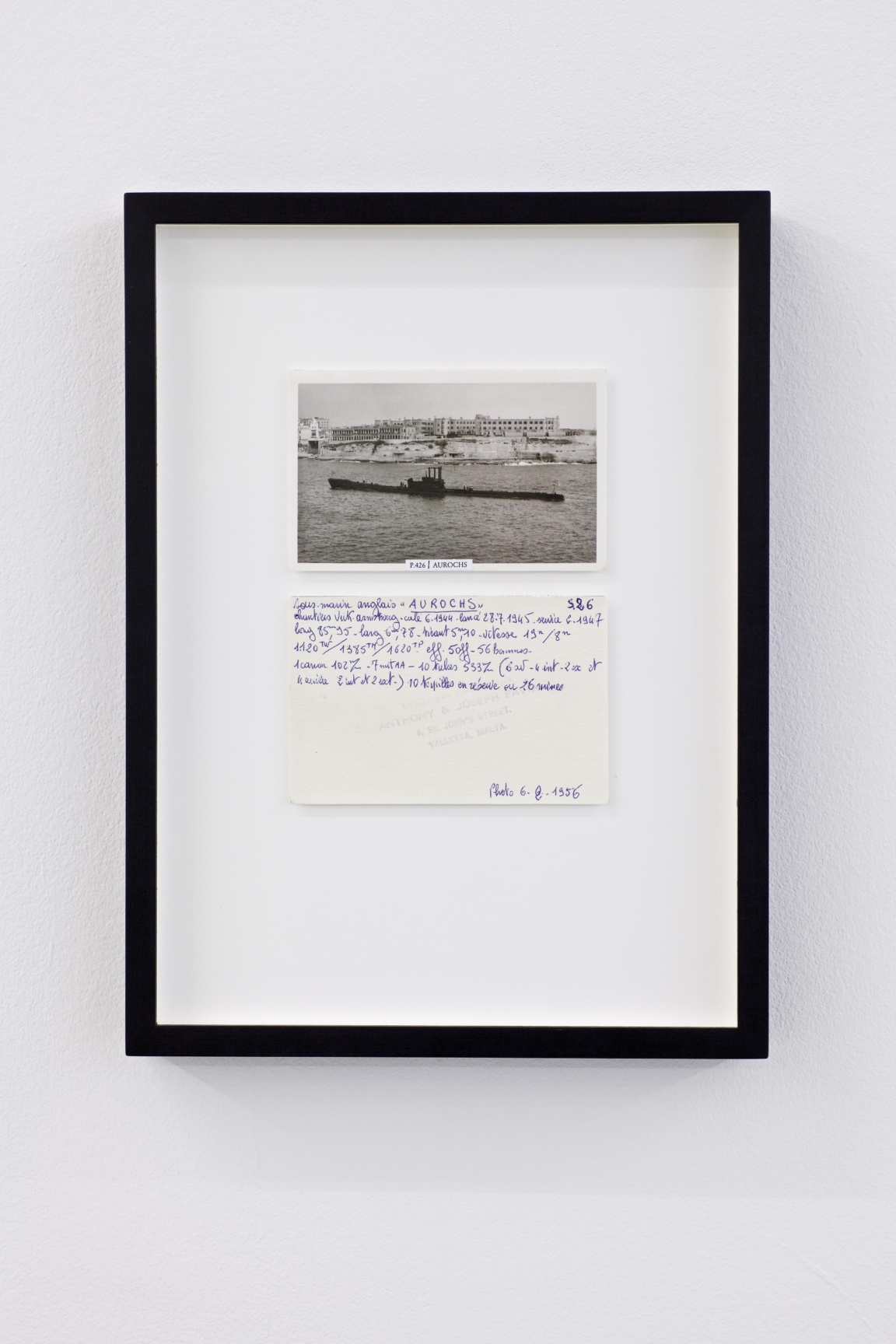

Only at second look the entire potential for interpretation of the works reveals and the observer realizes in reflection the power of his/her own view. This realization, however, is interrupted a second time by the loosely inserted series of quasi-documentary ‘interfering images’ and text that at first suggest a historic-scientific context: but is it comment or source, real historical document or fake?