Marijn van KreijAbstraction, Class, Education, Hacking, History, Information, Nature, Production, Property, Representation, Revolt, State, Subject, Surplus, Vector, World, Writings

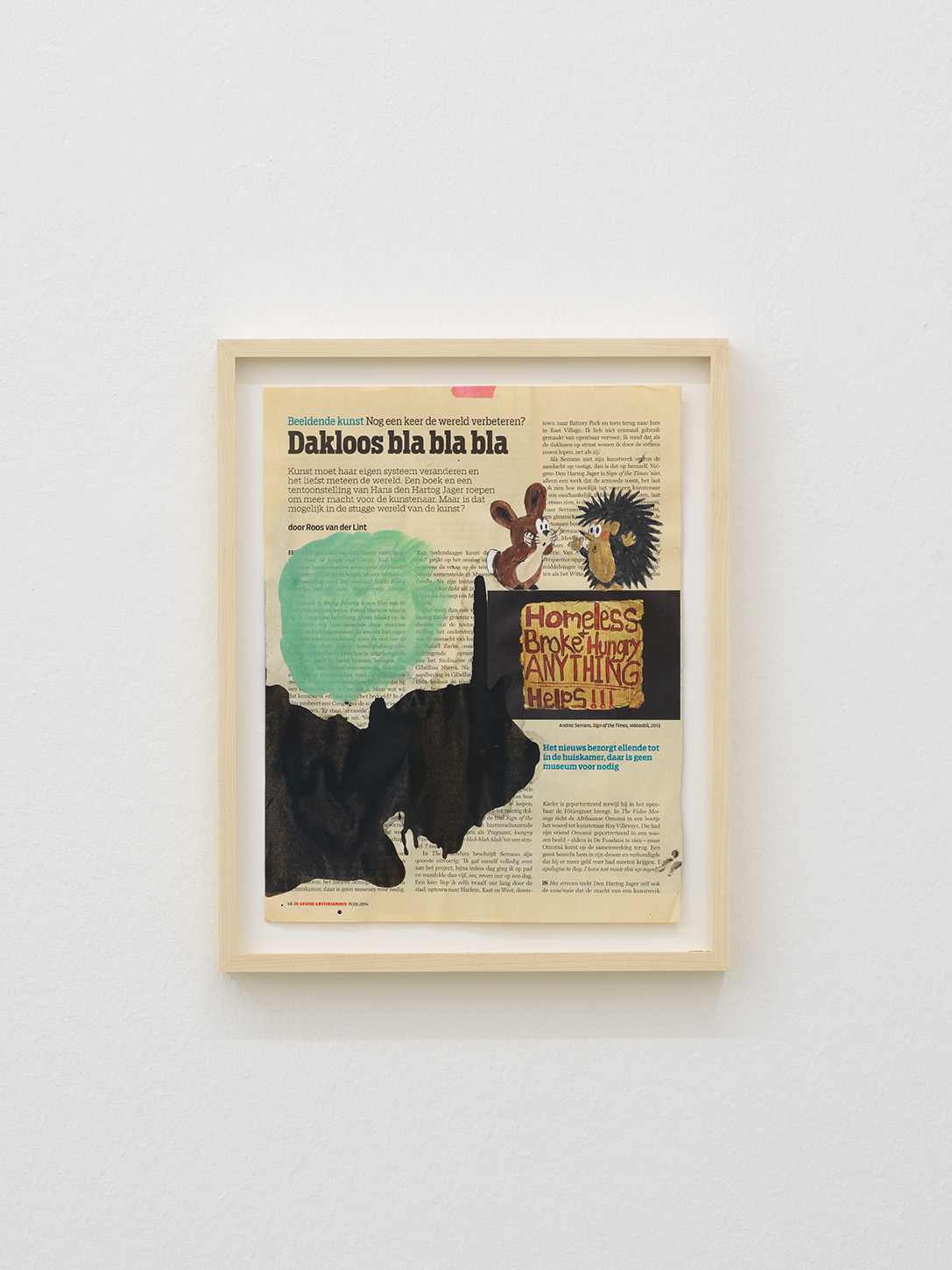

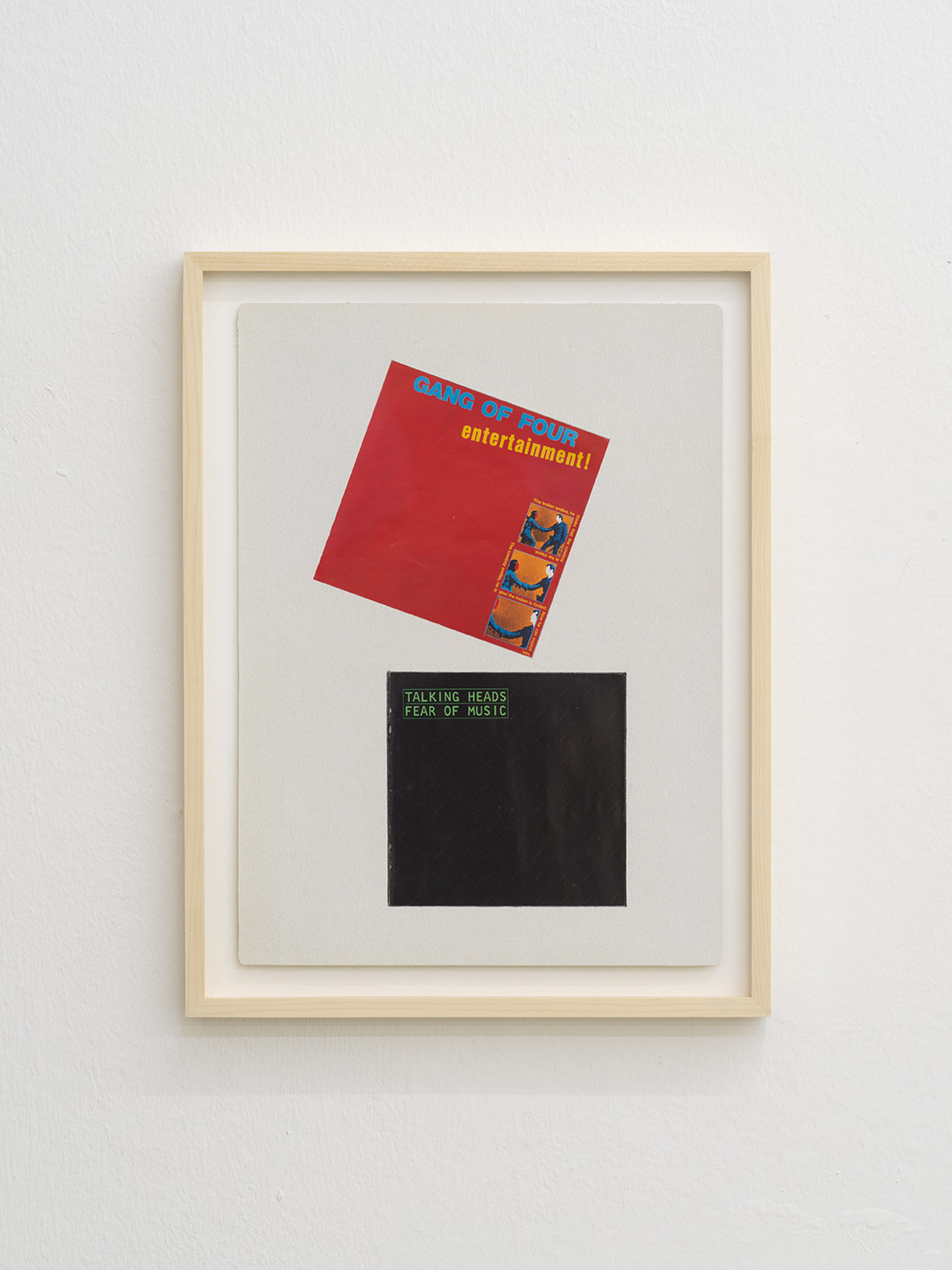

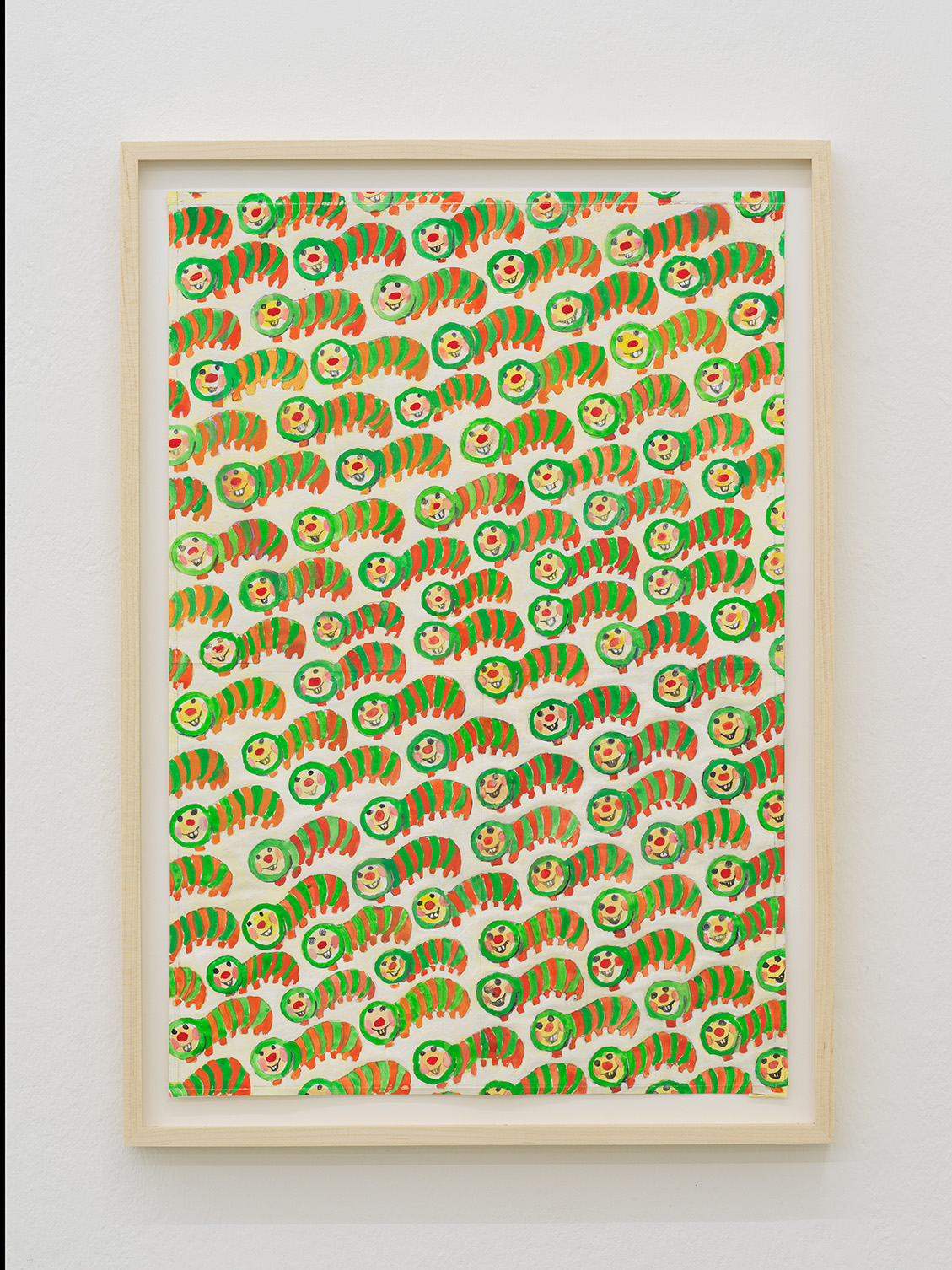

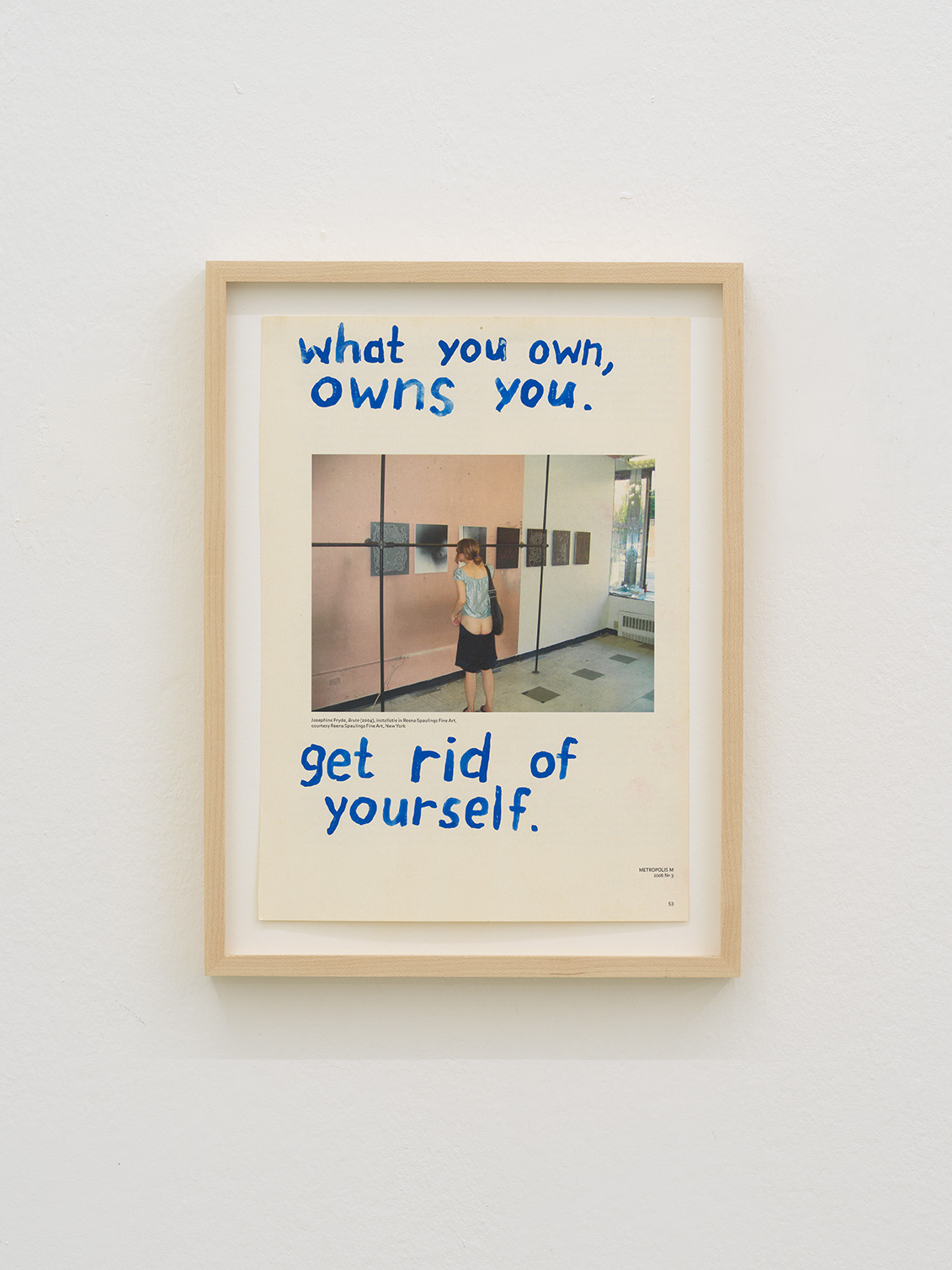

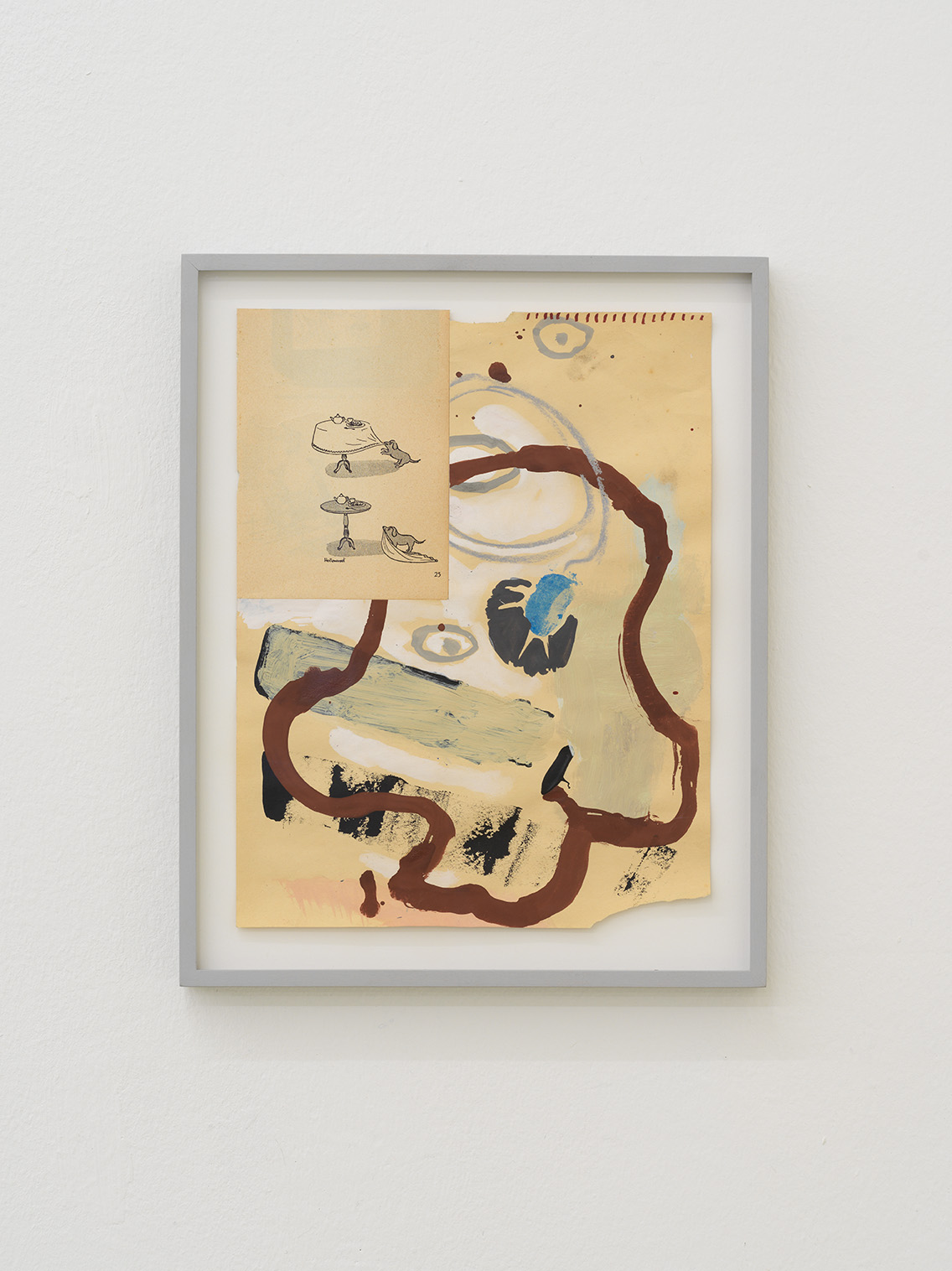

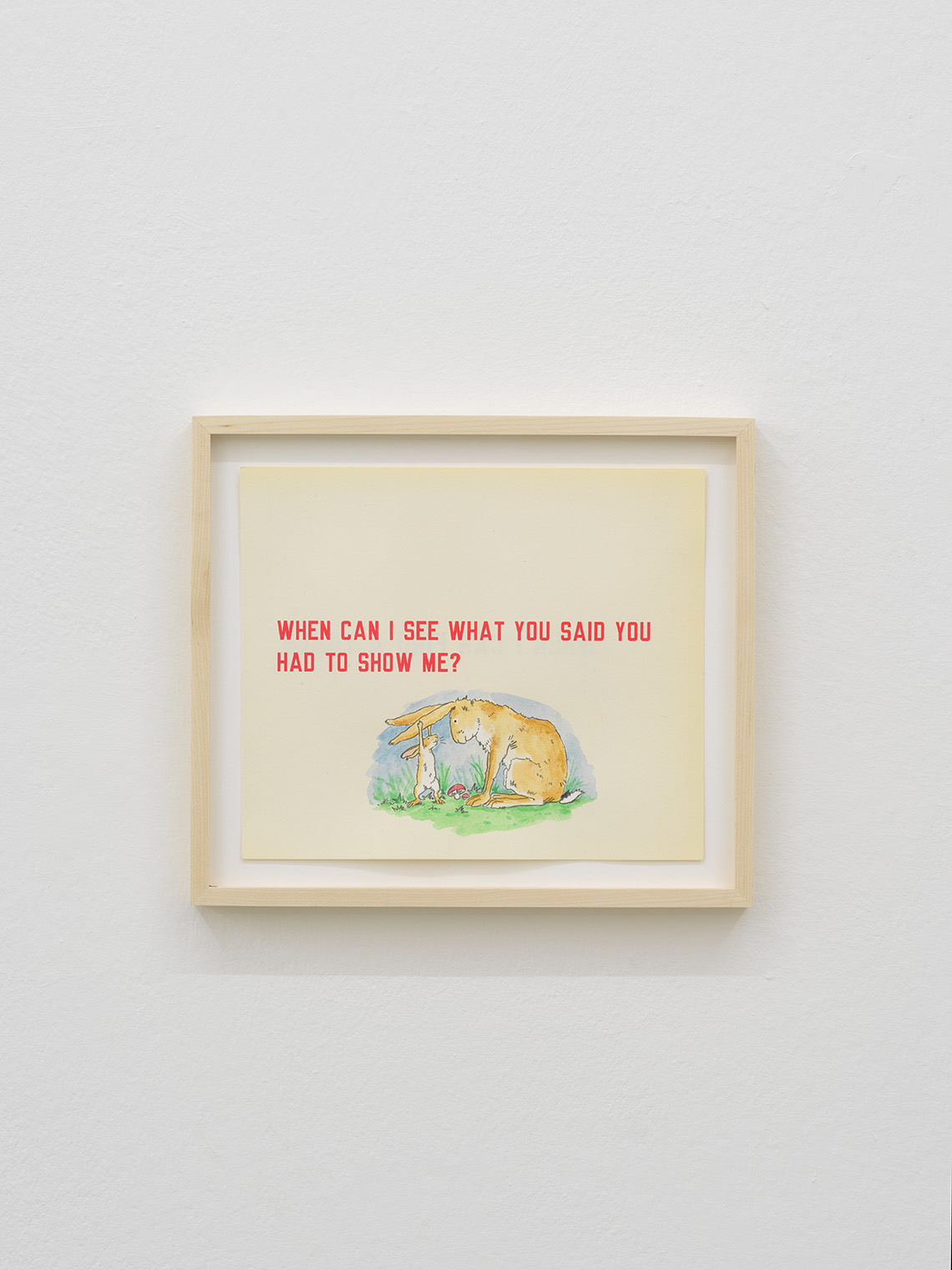

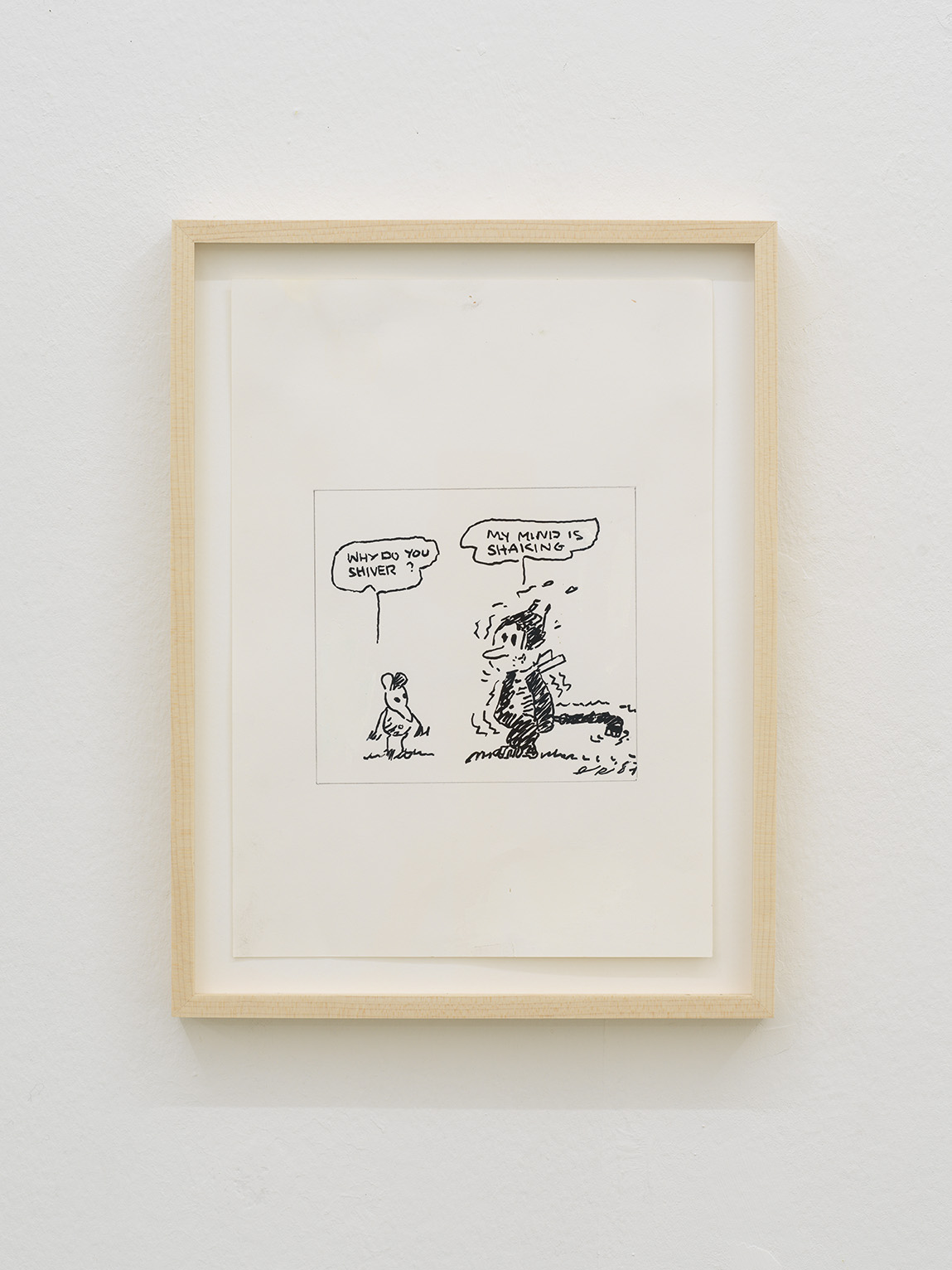

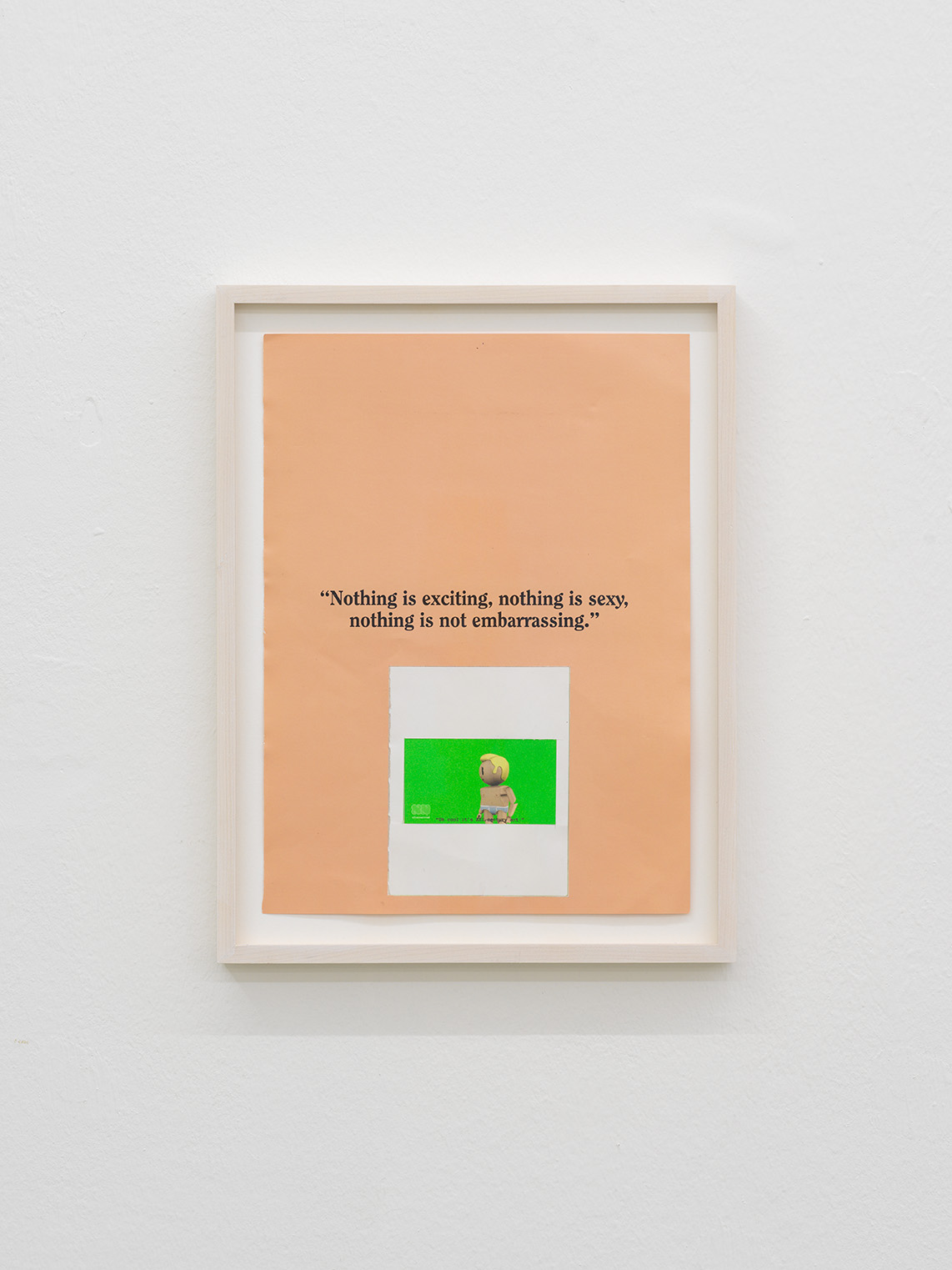

The title of Marijn van Kreij’s exhibition at Klemm’s – Abstraction, Class, Education, Hacking, History, Information, Nature, Production, Property, Representation, Revolt, State, Subject, Surplus, Vector, World, Writings – bears repeating, not to map it onto the show or suss out connections to McKenzie Wark’s A Hacker Manifesto (2004), from which the slew of weighty words is lifted, but rather to broach the artist’s relationship to language. Framing his show with this alphabetical list of nouns is a gesture indicative of the relationship between van Kreij’s work and the written word: it’s porous, entangled. And language is a focal point of the show, as found phrases crop up in many of the collages and drawings in gouache and pencil on paper or book pages exhibited here, appearing as comics, captions or in meme-ish juxtapositions of text and image. The selection of 28 drawings on view stretch from 2021 as far back as 2006, comprising a group van Kreij gathered intuitively. He anticipated the productive friction in staging this encounter between works which he has returned to sporadically over the years—mostly at in between moments, struck by the urge to simply make something. Previously situated as punctuation marks of sorts to his exhibitions, here the drawings are accentuated in turn by mobiles crafted from found materials. These wind chime assemblages introduce sound—or at least, its possibility—into the exhibition.

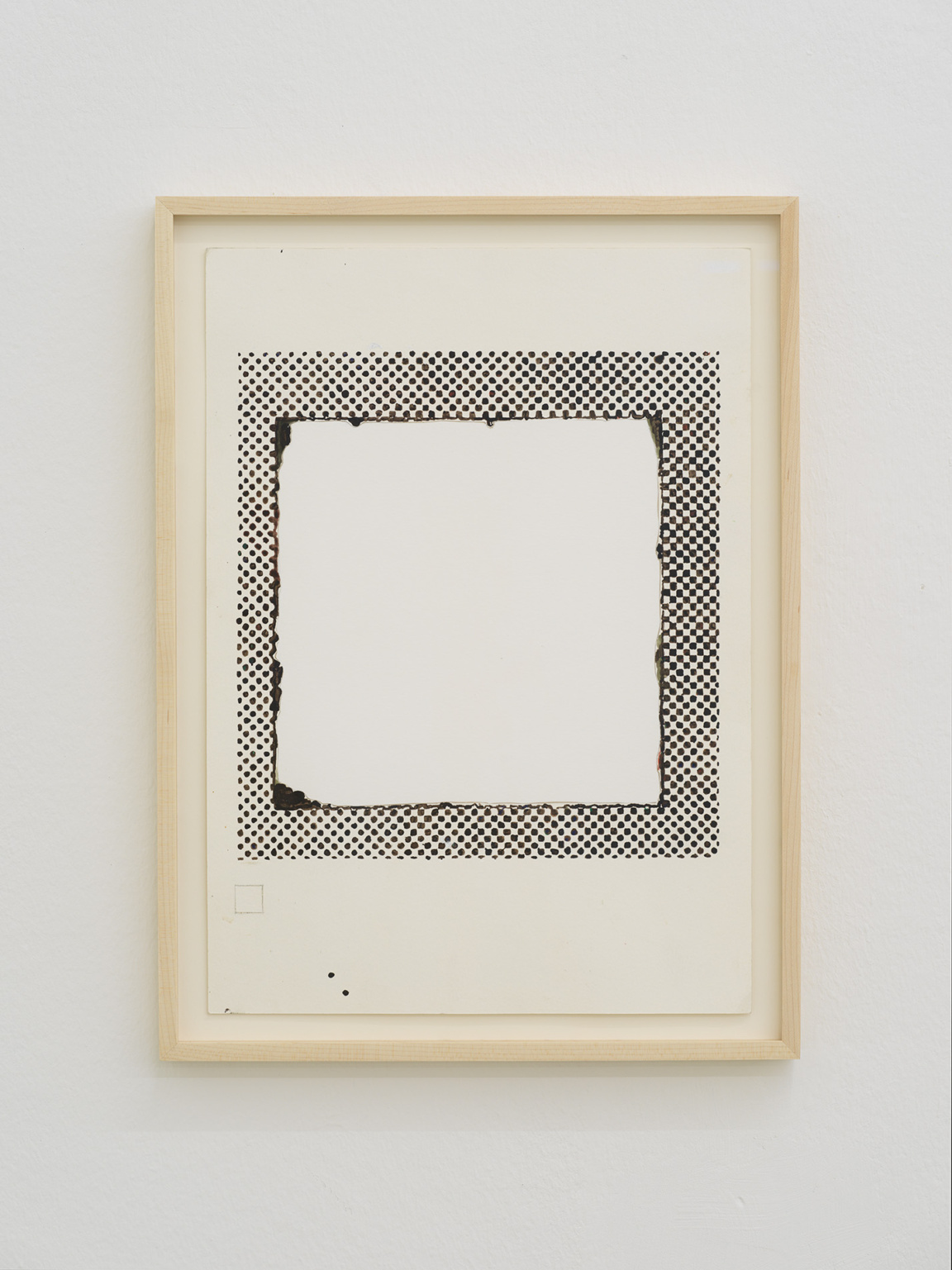

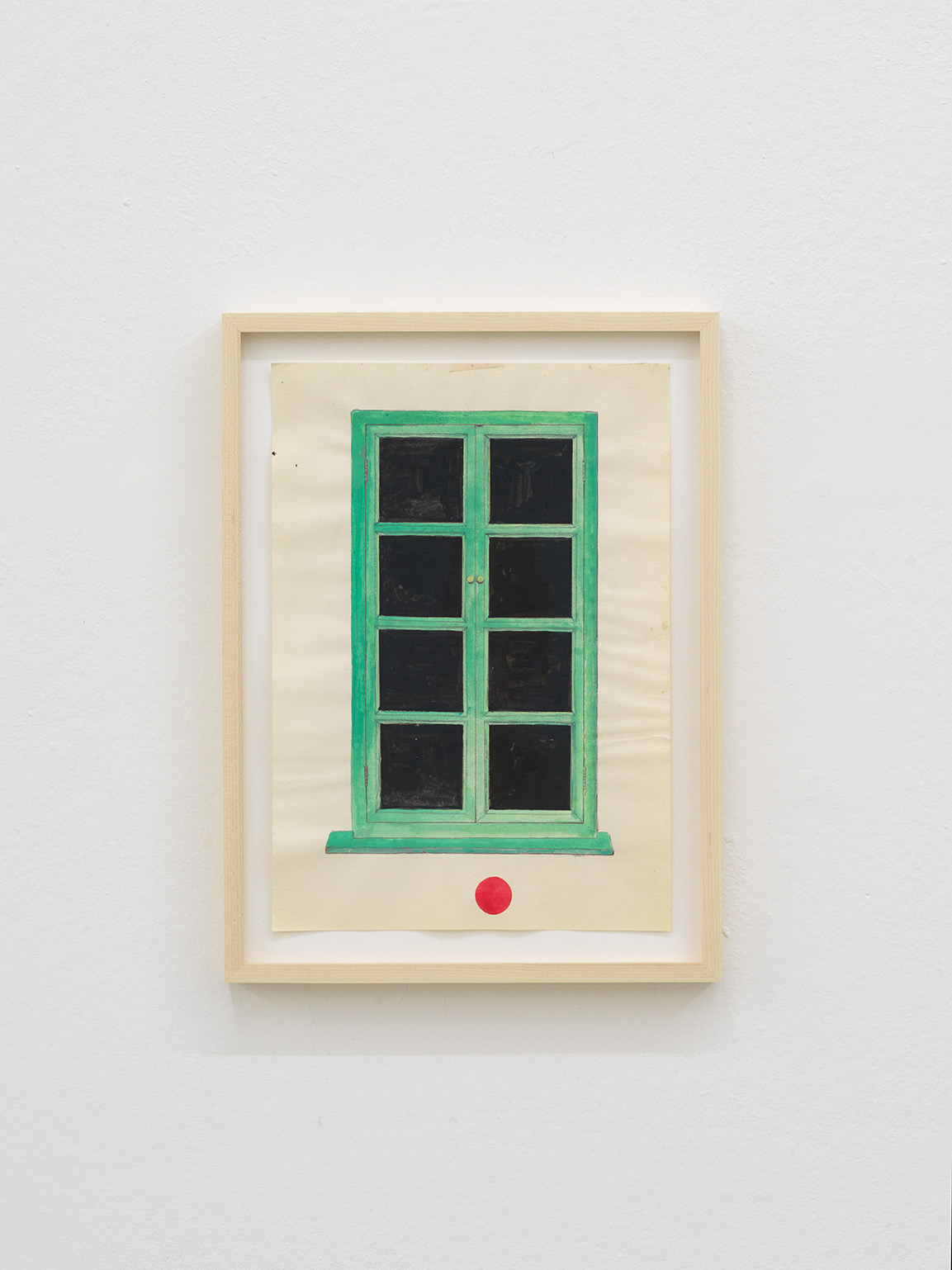

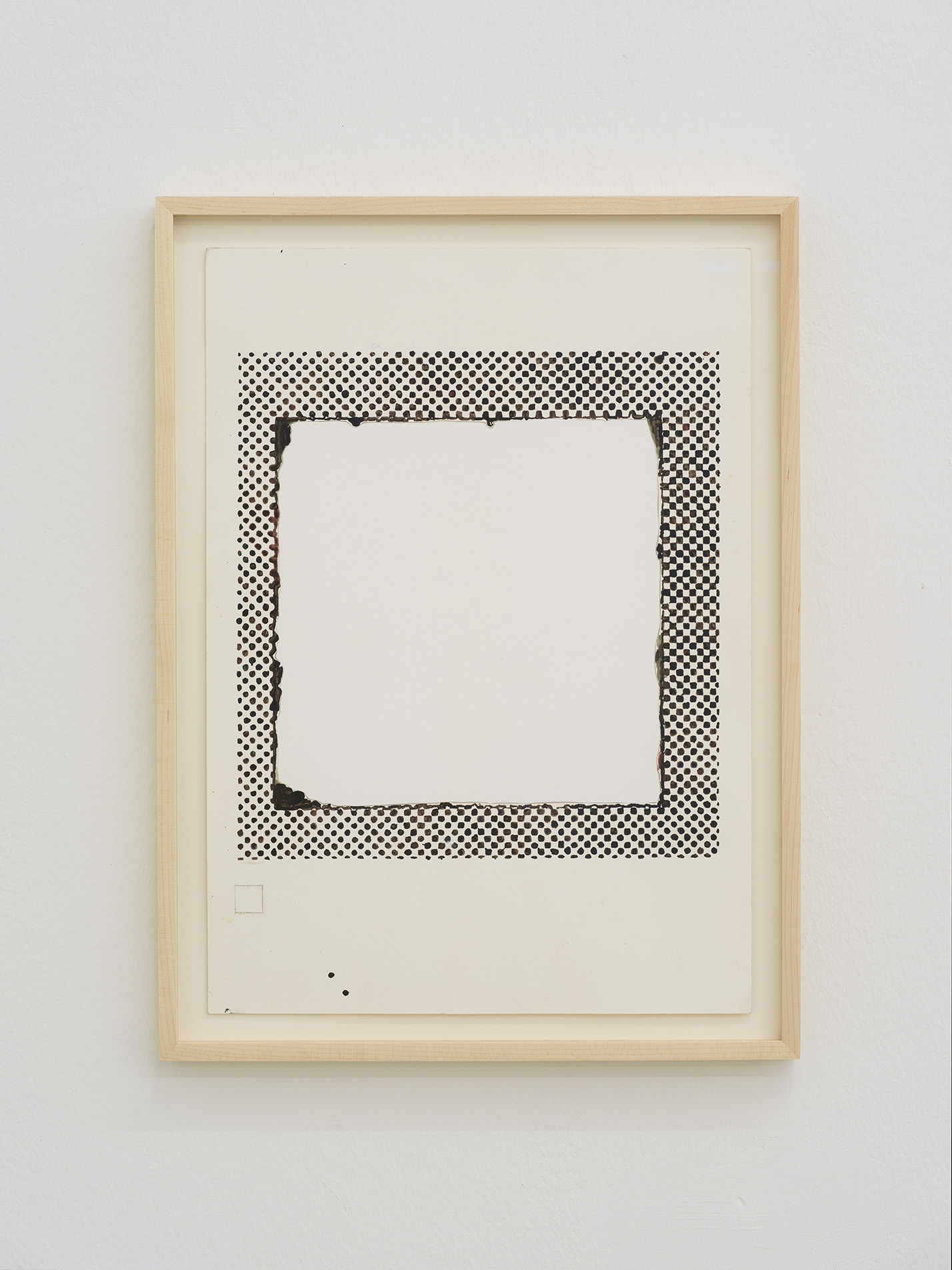

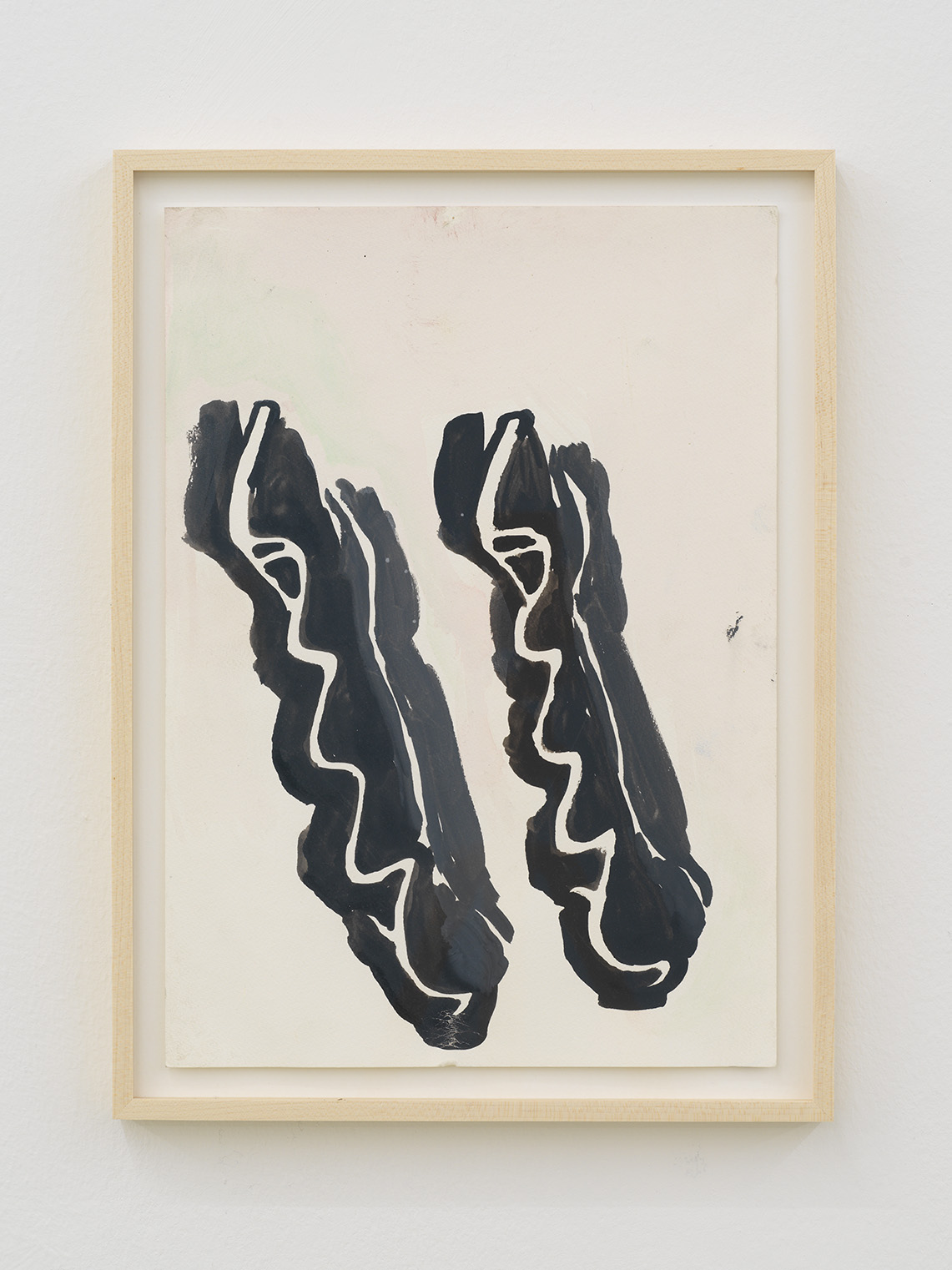

The potential clatter, as well as the borrowed and invented phrases or would-be aphorisms that populate many of his drawings, indicate his interest in facilitating outside incursions into his visual art practice. This is a stance counter to notions of art as some kind of sanctified realm. This posture is particularly striking given van Kreij’s attentiveness to the motif of the grid, which Rosalind Krauss famously classified as “impervious to language” in her essay published in October in 1979, “Grids.” Kraus asserted that its structure “will not permit the projection of language into the domain of the visual, and the result is silence. This silence is not due simply to the extreme effectiveness of the grid as a barricade against speech, but to the protectiveness of its mesh against all intrusions from outside.” Van Kreij’s practice and his handling of the avant garde’s favorite motif (from Kazimir Malevich to Piet Mondrian, Agnes Martin to Eva Hesse), chips away at Krauss’s point of view, as his grids coalesce with his collaged phrases and cartoons. And almost seem to talk back. In the 2020 work in gouache on paper, Untitled (Picasso, Las Meninas [group without Velázquez], 1957, Leaving), a crudely rendered figure appears to be actively either constructing or destroying a gridded structure, as if illustrating the “intrusion from the outside” supposedly proscribed by this form. Van Kreij also plays with the 20th century grid’s origin in the 19th century’s interest in windows (think Romantic yearning at window sills and Symbolist geometric panes) by compressing the two in works like the 2017 collage, Untitled (Parkett, Saul Steinberg, National Geographic, Window) in which a tight checkerboard grid opens at its center as if to frame a rectangular view of blue sky. In Untitled (Malevich, Zwart Vierkant, 1915, Het Onzichtbare Zichtbaar Gemaakt) (2012/21) black gouache marks against a white sheet also frame an empty center, as the precise, tiny rectangles give way to amorphous, rounded points, seemingly performing that classic conundrum of the grid: the inevitable fallibility of the human hand in its attempts at perfection.

Ad Reinhardt merits mention as another artist who worked across image and language in his abstract compositions and satirical art world comics, both of which van Kreij has referred to throughout his oeuvre. Where these two poles of Reinhardt’s practice remained distinct and developed inversely throughout the 1950s and 60s (his paintings became increasingly sparse, culminating in the monochrome black paintings, as his word games and iconology became progressively complex), van Kreij moves instead towards the cross-pollination of the visual and verbal, anathema to the late advocate for the purity of abstraction. Nevertheless, there is a shared sensibility. Imagine the note Reinhardt jotted down on November 4, 1957, as another series of words – like the show’s title, but verbs, this time – which hang comfortably around this series of drawings, tap into the ethos with which they were made, and make for an apt way to close:

Hold on, hold up, hold off, I don’t want to do anything, I forget myself sometimes, sometimes I get enthusiastic or excited, like any old eager beefer, but when I sober up I say to myself, hold on, hold up, hold off, lay off, lay up, lay down, lay aside, and things are the same like they seem all right, so retire, make on, make up, shake up, shake down, buckle up, buckle down, muckle on, mockle on, rockle on, goggle on, wockle away.

— Camila McHugh

Made possible with the support of Mondriaan Fonds.

press release (EN) | press release (DE)